Concerning the Burning

Is there a Star Trek ‘Theory of History’?

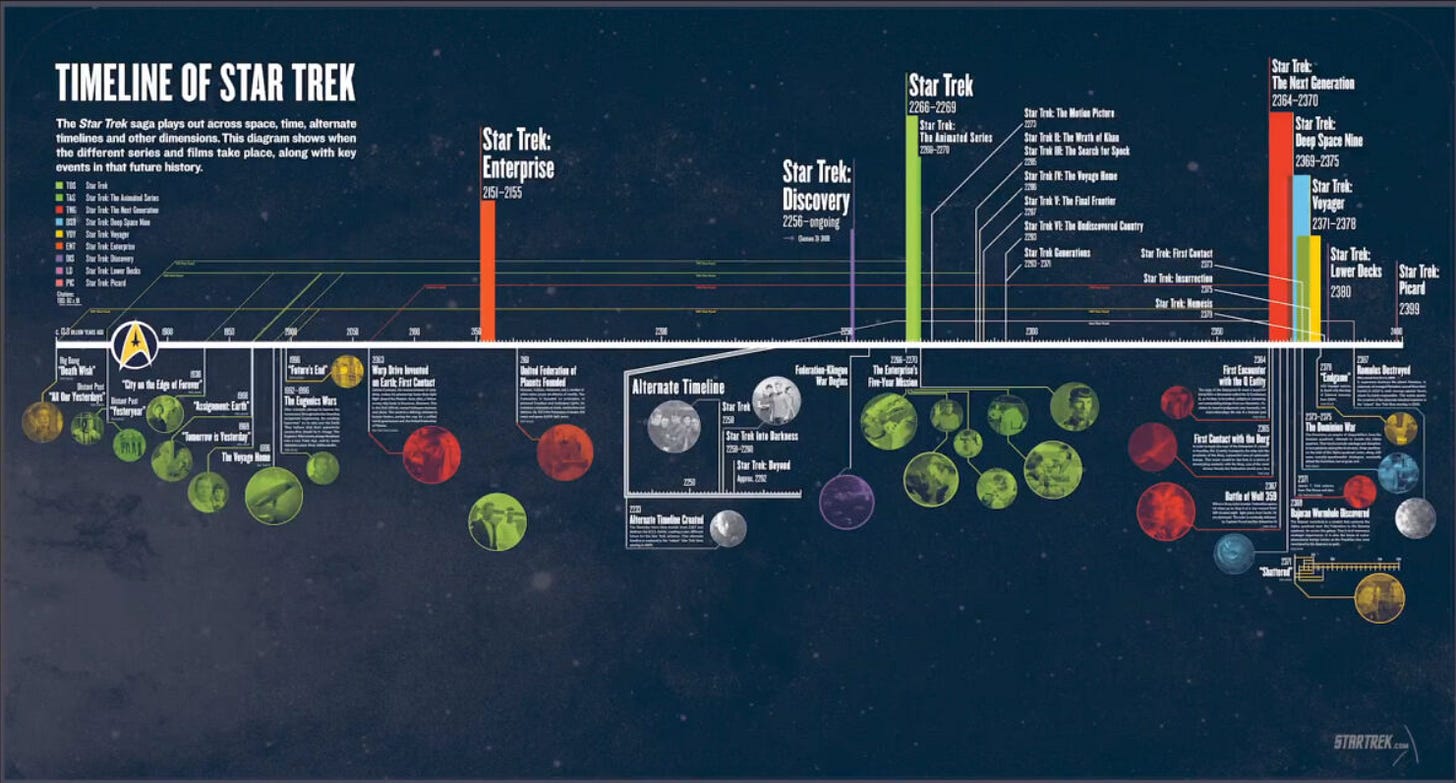

[Star Trek timeline from GiantFreakinRobot.com]

.

One thing Starfleet Academy does is bring our attention back to ‘the Burn’, in the aftermath of which the show is set. ‘The Burn’, of course, was a story-element of Star Trek: Discovery (2017-24). At the end of that show’s second season the starship Discovery travels a thousand years, or so, into its future and finds the Federation fragmented and banished from Earth, after a catastrophic event, called the Burn. At some point, and for mysterious reasons, all starship warp cores exploded, destroying their ships. Interstellar travel, which relied upon warp drive, has become dangerous, fragmented the many worlds and star systems—Discovery, which runs on a non-warp technology by which onboard mushrooms do something improbably efficacious and bizarre to the spacetime continuum, is not at risk. The Burn was, specifically, the sudden explosion of all the galaxy’s dilithium, a magic crystal or metal (I’m not sure which it is, although certainly it has nothing to do with the actual molecule made up of two lithium atoms, Li2) that keeps the interaction of matter and antimatter in spaceship engines balanced. Throughout Discovery s3 the mystery of what caused ‘the Burn’ threaded the episodes, and was finally resolved. It had nothing to do with Discovery falling through time. Nor, despite sharing its name with the first syllable of hers, did it have anything to do with Burnham. It’s possible the scriptwriters decided not to pin the blame for ‘the Burn’ on Burnham because, had they done so, they would have been obliged to invent a whole second galactic catastrophe called ‘The Ham’, perhaps involving bad acting. Instead a bonkers set of events was cascaded through Discovery s.3: involving a planet made entirely of dilithium, a spaceship crash-landing upon it just as one of its crew, a Kelpian, was giving birth, such that the baby develops a magic connection with dilithium as such—how? what?—that later pays into a circumstance in which this alien, growing annoyed, sets off a chain reaction in which all the dilithium in the whole galaxy explodes. We know the story.

When the Khi’eth crashed on a planet in the Verubin Nebula, Issa—knowing she was dying and that rescue was unlikely—created a vast holographic environment to sustain her son’s needs. Due to radiation exposure from the nebula while he was in utero, Su’Kal developed a connection with his surroundings; specifically, the planet’s large dilithium reserves. When he was approximately four years old, Su’Kal inadvertently caused the Burn when he emitted a powerful psychic shockwave, which triggered the nearby dilithium. The psychic scream was triggered by Su’Kal’s trauma of seeing his mother’s death.

The purpose of this post is not to relitigate ‘the Burn’ as such, absurd though the in-show explanation for it remains, and despite how clumsily the whole thing was handled. I assume it was scripted because the showrunners wanted to stage a longer-format ‘rebirth of the Federation’ story-arc (perhaps because the premature ending of Star Trek: Enterprise had robbed the show of doing the complete ‘birth of the Federation’ storyline first time around), and that such a renaissance requires a break from which the Federation could renaiss. That they had to pull so many levers with labels such as “nonsense”, “handwaving”, “made-up bollocks” and “quick-look-over-there!” to achieve this is not to the show’s credit.1

My interest is otherwise, viz.: whether it’s possible to extract a meaningful ‘theory of history’ from the multifarious, on-the-moment localised and centripetal, only-in-retrospect ‘will to coherence’ of Star Trek as a whole.

As far as that goes, we can note that there are various ‘theories of history’. It might be that history is just stuff happening, an ongoing churn of events, but perhaps there is something more shaped, more coherent going on in human global chronology. A theory common in the ancient world saw history as a narrative of decline, from a past Golden Age, through a diminished Silver Age, decaying to our present Age of Bronze. Conversely, there is the Whig Theory of History that treats history as a linear upward progression from barbarism and feudalism moving inevitably towards a glorious present of modern liberal democracy, constitutionalism, and scientific progress. David Hume, Edward Gibbon, Macaulay and, latterly, Francis Fukuyama argued for this notion of history as in effect a smooth upward progress. Marxist theories of history see it as a more conflicted series of class conflicts, although also on an inevitable progress upwards, towards Communist consummation.

In Star Trek and Star Trek: the Next Generation a theory of history is tacit. The future-setting of the show involves a much better world than our (then) 20th-century one: racism and sexism have been banished, poverty, war and disease overcome, money is no more and humanity is spreading through the stars. But the path from our now to this splendid future is not one of smooth, progressive ascent. On the contrary, from now to Star Trek’s future the show posits a retrogression: between the relative prosperity of 1960s Earth and the broad sunlit uplands of Star Trek: TOS intervene the Eugenics Wars (1992-1996), World War 3 (2054–2079) and a period of post-atomic horror (2049–2053). After this we get the invention of the warp drive by Zephram Cochran in 2063, the arrival of the Vulcans, the events of Enterprise and the ascension of Earth into the Federation.

In other words, the ‘theory of history’ implicit in Trek is: things do get better, but first they must get much worse.

Whether this represents a coherent ‘theory of history’ is perhaps debateable. But I think ‘the Burn’ fits here: from Enterprise, to TOS, to TNG and DS9 there is a clear sense that each series marks an advance upon the society, technology and possibilities of the one before. But then with Discovery, and leaping a thousand years forward, we find ourselves in an epoch of rebuilding after galactic catastrophe has set-back progress. And in Starfleet Academy this rebuilding is manifest, a world all gleam and shine, with even more advanced technology, and even more inclusivity and utopian vibing. The implication is: in order to progress we need to have a huge setback, and this disaster will somehow propel even more progress.

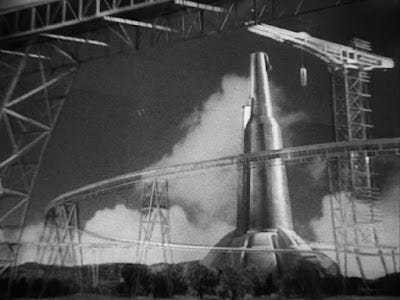

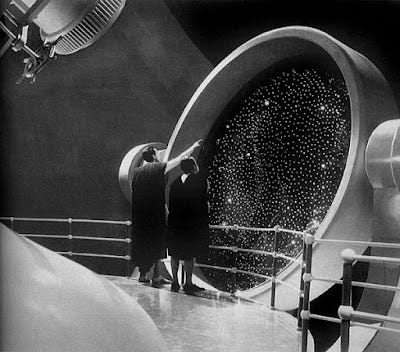

As a theory of history this derives, I’d argue, from H G Wells, and from The Shape of Things To Come (1933); or more specifically from its big-budget screen adaptation (co-written by Wells himself, directed by Alexander Korda) Things To Come (1936).2 Wells’s novel is a future-history that starts in the 1930s, then imagines a devastating war being fought across the world in 1940, a resulting collapse of civilisation, barbarism, warlords and piracy, until a new force arrives out of, of all places, Basra, Iraq: ‘Wings Over the World’, a group of dedicated scientists and technicians who have created a new advanced and indefatigable air-force which flies about the globe outlawing war, decreeing an end to individual nation states, and establishing a techno-utopian world state. The visualisation and designs of this last in the movie was hugely influential, and variants of it reappeared for many decades in modified forms as the template for cleanly antiseptic future utopian infrastructure in myriad SF films and TV shows, from Star Trek to Logan’s Run, from Doctor Who to the Westin Bonaventure Hotel.

This is what interests me: Wells gets credit for the accuracy of many of his ‘prophesies’ (he imagined the tank, coined the phrase ‘atom bomb’, foresaw both the 1st and 2nd World War, and his Anticipations (1901) is full of future-guesses that come right) but what he got wrong was precisely the shape of his future history, viz. that a gleaming utopian future awaits us, but in order to get there we first have to take a giant step backwards, into global barbarism, and only then leap gigantically forwards. That isn’t how the 20th-/21st centuries have actually gone.

It’s an interesting ‘shape’, certainly. Perhaps it speaks to people because they feel we can’t get there from here, so we need a ‘detour’; or perhaps ‘we will only band together if our back is against the wall, things must get worse before they can get better’. But it proved to be wrong. History from 1933 (and in the case of Trek, from 1966) to 2026, has not followed this path. Although maybe I shouldn’t tempt fate: maybe a period of eugenics warfare and posyt-atomic disaster is just around the corner.

It’s conceivable the original idea was to tie ‘the Burn’ to USS Discovery’s time-travelling and Burnham’s seeding of plot-coupons (that is, the seven mysterious time-travel signals that played so prominent a role in Discovery) and that the scriptwriters chickened out, for fear of making Burnham even less likeable that she was perceived as being. Although, you know: there’s nothing below Absolute Zero. That’s just a fact of the likeability temperature, energy and entropy scale. But whatever.

Are we sure that's not how the 20th century went? It might not have been a global 'descent into barbarism', but surely the most destructive conflict in the history of the species counts for something in that regard, and while utopia might not have followed, surely the end of classical imperialism, the advent of conceptions of universal rights, the beginnings of a global demographic transition towards longer lives with more calories, and a wild basket of new technologies count on that side of the roster too.

In fact, I've always thought the whole Trek future of Egenics Wars/WWIII followed by a great leap forward was explicitly a historical analogy to WWII and the boom decades that followed.

I may be the only person who actually likes Burnham. But this has me second guessing my affection for the character.